Three Warning Signs a Fall is About to Occur

"It was just a freak accident."

"There was no way we could have seen that coming!

If you haven’t heard something like this, spend a little time doing incident investigation in an occupational setting. Trust me, it won’t take long. Statements like these perpetuate the belief that accidents are beyond our control and there are no precursors to them, however studies seem to indicate otherwise. Certain behaviors – or warning signs – exist that should trigger an alarm to anyone paying attention.

Prior Violations

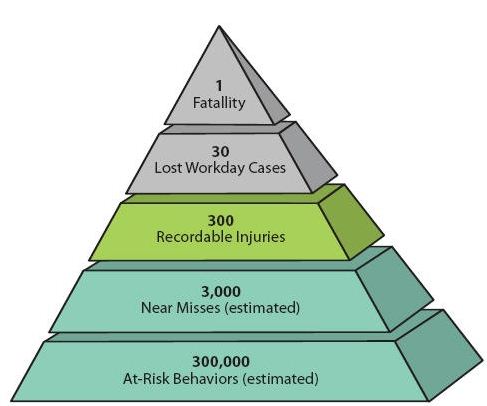

As safety professionals, we learn early on about the ‘Safety Pyramid’. This was an idea first proposed by H.W. Heinrich in 1931 that, when boiled down, showed that there were approximately 300 incidents for every major injury. Almost four decades and some terminology shifts later, Frank E. Bird proposed about 600 incidents for each fatal accident. The study, though, that is probably most relevant to us due to its chronological proximity is one conducted by Conoco Phillips Marine in 2003. This study showed that for each fatality there are 3,000 near miss incidents and 300,000 at-risk behaviors. That’s 300,000 opportunities (statistically speaking) to correct a problem before it becomes a fatality.

In other words, there are plenty of indicators that a ‘freak accident’ is about to happen. You just need to know what to look for. When it comes to falls, they are no different than other injuries or fatalities in this sense. An employee’s likelihood to fall is influenced by their behavior. If a certain employee tends to violate the rules, disregard his or her personal protective equipment, or generally wander around with the attitude that they are invincible and safety rules do not apply to them, look to them to be a potential victim. This is the person that has a higher probability of working at heights without proper fall protection (an improper anchor, an improperly worn harness, no fall protection equipment at all). This is the person that might walk out to the edge of the roof because they are ‘only going to be there for a second.’ This is the person that is going to do something to endanger themselves or others.

Should one of your ‘problem’ employees be assigned a task that requires them to work at heights, additional training may need to be held prior to the start of work or the disciplinary program might need to be reinforced. One way or the other, a company needs assurance that this employee is going to work safely, in order to avoid a ‘freak accident’.

Exhaustion

In today’s economy, companies are trying to do more with less. While production has crept back up, a large number of people who have been laid off since 2009 have not returned to work – at least not in the same capacity they worked before. Many companies were forced to streamline their workforce and, in the process, found that they could do just as much with fewer people. Sometimes, this results in overtime pay and sometimes it doesn’t, but what it results in every time without failure is eventual exhaustion. People get overworked. People have breaking points. As people approach this breaking point, their work begins to get sloppy. They lose the ability to focus. Their minds wander. Details get missed.

What happens when that detail is attaching your snaphook to your anchor point or simply watching where you step?

Recent studies have shown that drowsy driving is just as - if not more - dangerous than drunk driving, yet some employers feel they can continue to work their employees for long shifts over long periods of time without any adverse effect. In reality, their ability to work will be impaired just as much as their ability to drive. Add your employees’ extra-curricular activities (believe it or not, they do have lives outside of work) on top of these long hours and you’re asking for an accident.

Complacency

Sometimes, an employee can be their own worst enemy. Getting used to a job or feeling you know everything about it can lead to a level of complacency that could become dangerous. Let’s look back at a famous historical disaster – the Titanic. The largest ship in the world at the time was sailing through the north Atlantic and Captain Smith had iceberg warnings in his hand. They were going faster than they had intended to go, but on they went. Captain Smith believed that, should they encounter an iceberg, they would be able to turn in time. This might have been true on any of the ships Captain Smith had previously sailed, but the Titanic was larger. In addition, the seas were so calm that there were no whitecaps breaking at the base of the iceberg. By the time the watch saw the iceberg, it was too late. Captain Smith’s complacency was fatal.

By the same token, workers in every field can get to a point where they are so comfortable with the job they do, that they begin to do it on “auto-pilot”. They feel they know it “inside-out”. They may not only be unwilling to listen to advice or constructive criticism, but they even stop applying their own critical eye. Things, in their mind, are the same today as they were yesterday and the day before. Changes in process, tools, personnel, or environmental conditions may go unnoticed. Perhaps there’s always been a railing where they have to work, but today there isn’t. Maybe one of their co-workers has been replaced by somebody new. Maybe somebody leaked oil on the ground. Regardless of what the variable is, it gets missed. When a worker stops paying attention to these things, he or she increases the likelihood of an incident, and a fall is no different.

Conclusion

Granted, if somebody didn’t know what to look for, some of these precursors might easily go unnoticed, but the fact remains that they are there. A good safety professional must not only keep an eye out for these things, but must also ensure that other management personnel are aware of them, too. A company should be implementing programs that battle complacency (such as daily job briefings and management oversight) and, at the very least, be reminding employees to evaluate their tasks and work areas as often as possible. Near-misses should be reported and somebody should be reviewing all incident reports and safety violations for trends. Work hours should be reviewed. Are the extra shifts necessary? Is one employee overloading on hours to get overtime pay while others aren’t? Begin looking for these precursors and you will be on your way to doing the most important aspect of a safety professional’s job: incident prevention.